On the corner of Cross Street a lonely saxophone is keying

a sombre tune. People weave their way through the crowded streets to its slow

gentle rhythm. In their solemn silence people wade into St Ann’s Square, row

upon row drawing to a standstill.

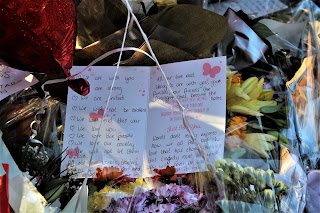

The sea of flowers swelling

minute by minute, while inch by inch tributes are etched in chalk. In each

framed photo, in every soft toy, in the flicker of each candle; a wounding

truth.

As shiny balloons danced in the

evening breeze, I witnessed the shared grief where stranger hugged stranger,

and those from the very young to the very old tried to comprehend. Struggling

to make sense of what happened, I heard a mother tell her daughter, “the

children are now singing with angels” holding her a little tighter. Children

holding “We love Manchester” placards, and babies still too young to understand

I looked into their innocent eyes and wondered, how do we explain such barbarity?

How do we heal? How do we move on?

That Friday evening, on the cusp

of Ramadhan, one of the most sacred months for Muslims worldwide, a myriad of Muslims

converged on St Ann’s Square to hold a vigil. Organiser Fesl Reza Khan told me

“its aim was to remember those who lost their lives and show solidarity with

bereft families and survivors”. Zahid Hussain, poet and author recited his poem

“Mancunian Way” to a growing crowd, ending with an eruption of

rapturous applause. A young man took the microphone and the lyrics of “WonderWall”

rang out leaving people in floods of tears. The ebb and flow of emotion, from

pride to pain, surged through. The nostalgia of Manchester’s great history,

from music to movement and change, seemed to be the glue binding people from

all walks of life. The symbol of the “Bee”, which represents Manchester, was reflected in the low humming of communication between people who beavered to aid

one another.

Speaking with many who had

attended to show their support, one sentiment struck me the most, “humanity

mattered more than anything else”. After all, we are flesh and blood, we bleed the same, as do we grieve for any

innocent life lost; be that here on our doorstep in Manchester or London, or in

places like Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Libya, France, Belgium,

Germany or Sweden.

While meandering my way through

the crowds I witnessed fellow community activists and humanitarians doing what

they do best, being present and offering empathy. All week I had heard from

friends who had organised food distribution, transport, and who had provided

refreshments to those waiting to hear news of loved ones in hospital. I was

told about the young girls from a local Muslim school who distributed roses in

their local area, and about children from a North Manchester mosque who were

walking for peace to lay tributes at the Arena. I heard about the first responders

who dropped everything, rushing to the hospital to offer assistance, delivering life-saving treatment to those wounded. Doing what any other human being would

do, help and assist.

I spoke with Emma mother of one

of the children who survived Monday's attack “you see things happen across

the world but never think it would happen here”. She went onto say “I love how

everyone has come together. Every one of all faiths and religions speaking to

one another and helping one another has been amazing.”

No matter what our race, faith,

ethnicity, gender, disability or sexual orientation “humanity” transcends,

speaks a universal language, and unites us. Sadly, not all experience the world

this way, and use tragedies like this to peddle their own divisive ideologies.

I spoke with people who had already experienced the backlash; a woman who was spat at in the street, a man being blamed for what

unfolded on Monday and the days that followed, and a child being called a “terrorist”.

I heard from a mother who felt fearful of leaving her home, and another who was

left feeling shocked and shaken after witnessing one of the numerous raids across the city

and wider afield. “It was terrifying. I saw many plain clothed police

officers wearing masks, holding huge guns pin a young man to the floor and

handcuff him, I came home feeling sick to my stomach” said Muslim grandmother

from Whalley Range. “It fills me with dread and sadness, and I wonder why would

anyone do such a thing?”

This question remains at large.

Why does a person decide killing is justified? What does it achieve? Some

argue that foreign policy is to blame, while others claim its religious

fanaticism. Some believe its mental sickness, while others think it's revenge. It’s

a question that cannot be ignored and needs in-depth analysis and research to

be wholly understood. Meanwhile, many worry there will be a continued “othering”

through laws which further marginalise, stigmatise, and criminalise one

community over another. I don’t have the

answers, but what I do know is this; be it Abedi or Breivik they only represent

their criminal selves.

In the words of Andy Burnham “This

is an extremist act and the person who did it in no more represents the Muslim

community than the person who killed Jo Cox represents the white Christian

community.”

As the fading sun

bathed the tops of buildings of St Ann’s Square in its golden light, the burst

of coloured blooms reached out to the sky. I felt pained as a mother, pained for

the backlash experienced by friends and pained as a Muslim for what may come. I

feel pained knowing terrorism hasn’t and will not discriminate, and I am just

as much of a target as anyone else.

Cheeks wetted by

tears I mourn; I mourn for the lives lost in Manchester; I mourn for the

needless lives lost across world; I mourn for them all.

©Aisha Mirza